Oxenhope

Online

Oxenhope

Online

|

|

|

|

Taken from 'A Brief History of Oxenhope' published in 1996 by David Samuels with many local contributors. Proceeds from the sale of the book are to support the Multiple Sclerosis action groups.

Preface

Snippets from Past Oxenhope (David Samuels)

The History of Oxenhope (Mr R Hindley)

Daily Life (Mrs Freda Feather)

Life on a hill farm (Mr Joe 'Bodkin' Feather)

Mill Life (Mrs Lucy Shackleton)

Village Life (Mrs Winnie Cowgill)

Education (Mrs Pauline Sheffield)

The Parish Church of St. Mary the Virgin (Mrs Margaret Hindley)

Religious Life in Oxenhope (Mrs Norma Mackrell)

Children started work in the mills at 12 years of age, as half-timers, with every other week at school in the mornings and in the mill in the afternoons, then alternate weeks the other way round. This was until they were 13 years of age and could leave full-time education. All employment, whether full- or part-time, was dependent upon a satisfactory report from the school authority which issued the child with a certificate to say he or she had attained a certain standard.

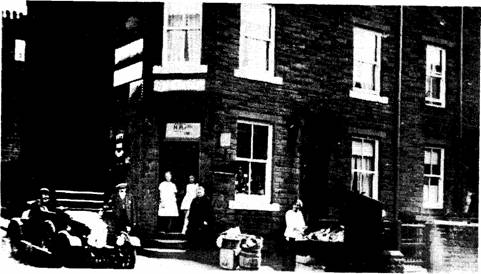

Greengrocer's

shop : Corner of Beatrice Street and Lower Town

There were several mills in Oxenhope, mostly woollen mills. Merrall's (later Hield's, now demolished with Leeming Water housing estate built on it), had two mills in Oxenhope. Fearnley's (now West Yorkshire Weaving) also had a small one at the side of Merrall's on Lowertown. There was Bancroft's at the bottom of Denholme Road and one by Old Oxenhope Hall. Weaving mills were at Brooks Meeting (now Tankard's), at Leeming and at what was to become Airedale Springs (now empty and unused).

Work started at 8am. A buzzer sounded at 7.55am, the workforce went into the mill, then the door was closed and locked. If anyone arrived later than this, they had to wait until the door was opened again at 9am, and lost an hour's pay.

The noise inside was frightening to anyone not used to it. The machines were driven by long leather belts which would stretch the length of the room, or shed as it was known, and wrapped around huge wheels. The ends of the belts were fastened with metal clips (rather like staples), and if any of these gave way, due to wear and tear, the flying leather could, and did, cause serious injury.

Despite the heat, the youngsters wore black overalls, with the girls also wearing black, knitted woollen stockings and clogs. Hair had to be kept fastened back out of the way of machinery, which in those days was unguarded and accidents were commonplace. Loose clothing, like the short smocks worn by the men, was easily caught up unless the greatest care was taken. The smell of lanolin, the natural wool oil, clung to clothing, and grease from the machinery made floors very slippery as it soaked into the floorboards. All this made the mills a serious fire hazard.

Children, both boys and girls, started as doffers, that is

removing the full bobbins from the spinning frames and replacing them with empty

ones. For this they received 1s 6d (7.5p) per week. They were supervised by

older ones who had become proficient at it and then graduated to spinning. The

many and varied processes in a woollen mill all required nimble fingers and a

keen eye. Broken threads had to be joined with a neat, flat knot. A clumsy knot,

known as a slub, would be spotted on inspection at the end of the weaving

process, marked with chalk and had to be removed and repaired

by the burlers and menders. These lengths of cloth, or pieces as they were

known, were 70 yards long, undyed, and the inspector could identify which

spinning shed they had come from so that the careless spinner could be

reprimanded.

Drought at Leeshaw

Reservoir

During the economic recession resulting from the coalminer's strike, boys took handcarts up Hillhouse Edge to the peat hills opposite Fly Flatts reservoir. There they cut peats, and because it was wet, it was left to dry out until the following day, when they would go back to collect it and cut more for the following day. Often they would find that someone had taken their stack of peat, so would help themselves from another stack.

During the Second World War when woollen cloth was in demand for uniforms for the Services, work started at 6am. At 8am the workers ran up the Catsteps for breakfast at the church, then back down to resume work at 8.30am. Lunch was 12.30pm -1.30pm, for which they had to go home or take sandwiches, then finish for the day at 5.30pm. Saturday mornings were always worked, and at the height of production, the afternoons as well.

Holidays were one week at Keighley Feast, and two days each at Christmas, Easter and Whitsuntide - all unpaid. The millowners gave the workforce a 'treat' once a year, by hiring a char-a-banc and taking them, usually, to Blackpool. The youngsters went on one day as they were the noisiest, followed by the older ones on another day, while the overlookers had their own trip. Segregation was rife, as each group thought themselves superior to others. Overlookers thought nothing of chastising an unruly youngster, with a leather strap if he thought fit. Workpeople had few rights. Yet most of them were happy in their own way, as they 'knew their place', and had no hopes of, and didn't expect, anything different.

After the war mills closed down because the khaki cloth was no longer needed in such quantities, and local people had to walk into Haworth to collect their dole. During this time the mills were cleaned. The boys would fill a bucket with hot water and alkali (probably caustic soda) and mop the floors. The grease rose from the wood as a thick green slime and the girls put sacking on the floor, laid on it, and scrubbed this mess from under the machines. Then the machines themselves had to be cleaned by rubbing them with emery paper and paraffin.